In October 2019, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Extreme Poverty, Philip Alston, made the following statement: “citizens are becoming ever more visible to their governments, but not the other way around.” Federica Donati set out to analyze the Prime Minister’s Question Time (PMQs) from 2010 to 2020 because it is deemed to be a way of subjecting the work and policy of the government to both parliamentary and public scrutiny. In the research, Federica was able to rely on prompt email responses from the House of Commons services, which provided the answers in just a few hours. What follow is a brief introduction on what the question time is and how it works; the results of the study are available in these summary tables.

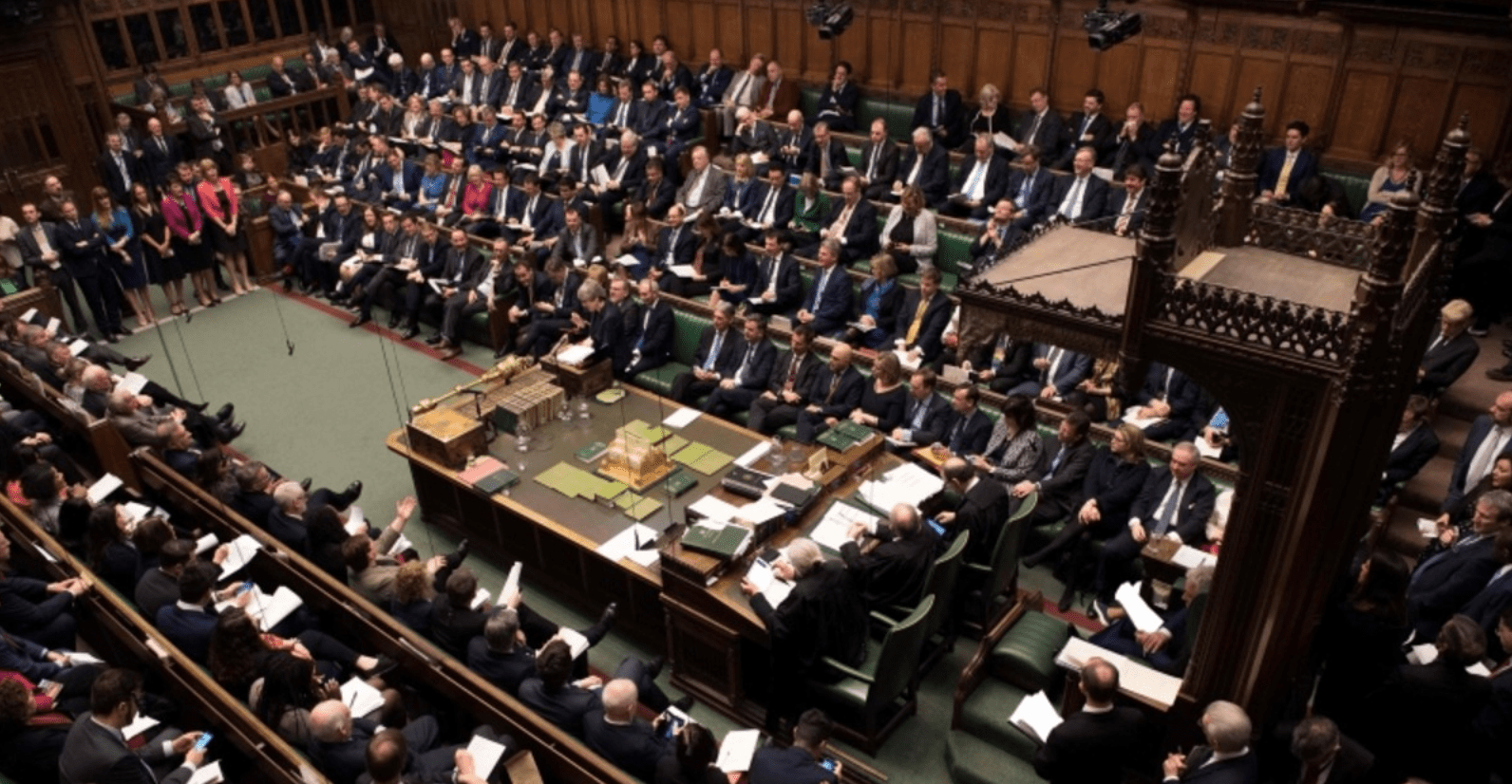

Question Time is held regularly in the House of Commons from Monday to Thursday, and it is an opportunity for Members of Parliament (MPs) to ask direct questions to the Government. Each Wednesday at noon, it falls upon the Prime Minister (PM) in person to face questions from MPs. Prime Minister Questions (PMQs) usually last for around 30 minutes but, in times of ‘crisis’, for example in the case of the COVID-19 emergency session on 25th of March 2020, the PM can be held to account for up to an hour.

The scenario that arises during the time of parliamentary questions is a direct confrontation with the executive; MPs can present issues of concern raised by their constituents, or question

the PM about the adoption of specific measures or ask for clarifications on PM’s own engagements. Crucial to the running of the PMQs is the figure of the Speaker of the House, whose role is to invite MPs to table their questions, whilst maintaining order during the parliamentary debate, allowing a balanced representation of majority and opposition parties, as well as ensuring gender equality of representation during the proceedings.

MPs’ questions can cover a wide range of issues, including concerns about the NHS (National Health Service), problems regarding security, questions about immigration, environmental or labour policy, the smooth running of public transport or schools, or, more recently, the handling of the Covid-19 crisis.

Normally, the MP starts the session with a routine question, namely the engagements question;

it is a formal question, known by the PM, and considered “open” as it gives to the same MP the opportunity to ask a further question. Technically, this second question can be about any topic, though more often than not, it will be a follow-up question on the same topic of engagements. In this case, the MP will table the so-called supplementary question. At this point, once the PM has provided the list of his or her engagements for that particular day, the Leader of the Opposition and the Leader of the third largest party may decide to table a substantive question, the meaning of which will be specified later, or an additional question in the context of the engagement question. It is very unusual for the Leader of the Opposition, or the Leader of the third largest party, to ask the Prime Minister a substantive question at this stage, as the Leader of the Opposition is permitted six supplementary questions in total, which can be posed even in different moments within the same session; the Leader of the third largest party, when present, is allocated two. From 2010 to 2020, the Leader of Opposition asked about 1961 questions, while the leaders of the third largest party tabled 340 questions (we should bear in mind the coalition government between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, which ran from 2010 to 2015)

In addition to supplementary questions, the content of which the PM has no formal prior notice, MPs can also table a “substantive question”. These questions are identified with a question number and they will have to be printed in the Order Paper, thereby giving the opportunity for the PM to study their content in advance and formulate his response. In tabling the question, the MP will also have the opportunity to ask a supplementary question that must be on the same topic of the original question and, in consideration of the fact that it is not printed in the Order Paper, the PM will be required to give an impromptu response.

As a final observation, I would like to point out the case where the PM is absent and not able to participate to question time; in this case, the Deputy Prime Minister or a senior minister will be called upon to answer. Between 6th of January 2010 and 6th of May 2020, there have been 4 Prime Ministers. Gordon Brown was asked 246 questions, David Cameron 5,305, Theresa May 3,012 and Boris Johnson has so far responded to 442. The PM has been substituted at PMQs 25 times by, for example, the Deputy Prime Minister, Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Leader of the House of Commons, First Secretary of State and Head of the House of Commons, First Secretary of State and Minister of the Cabinet Office, and First Secretary of State and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

What makes the question time so interesting is the fact that, in most cases, the PM receives, at least in theory, no formal prior notice on the questions that will be asked. However, in practice, the PM will have received extensive information from government departments about possible subject matters that might arise during the parliamentary debate. In the decade taken into consideration, there were 326 sessions and approximately 9770 questions, of which 4250 the PM had prior notice of the subject matter and 5520 of which the PM had no formal prior notice. The average number of questions asked during a session of PMQs in this ten-year period is 29.9.

Intended as a back-and-forth question and answer session between Parliament and Government, question time represents a key pillar of the British political system. Often embellished with instances of quirky English humour, PMQs allows Parliament to exercise a fundamental function of control over the executive, by calling them to account for their actions. It is an important cognitive tool within a democracy, an instrument that can ensure citizens their right to transparency and their right to know of which, unfortunately, they are not always able to enjoy.

Federica Donati