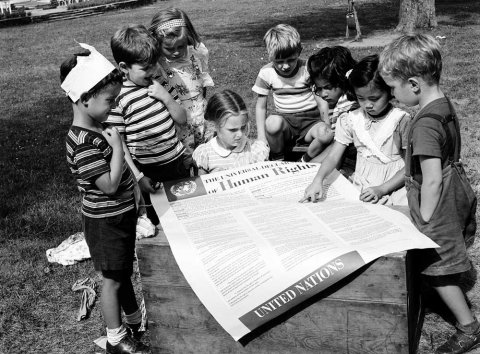

On 10 December, Human Rights Day, the world commemorates the adoption by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, this day 69 years ago. It is worthwhile emphasising that human rights and the rule of law are universal, in that as the UN Declaration stipulates, “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”.

We believe today is a good day to re-read an op-ed by Louise Arbour, former UN Human Rights Commissioner, published in the New York Times on 26 September 2012, on the crucial distinction between “rule of law” and “rule by law”.

The Rule of Law

Louise Arbour

The rule of law.

Everyone believes in it and wants to promote it. But as a high-level meeting convened by the new session of the United Nations General Assembly gets set to discuss the rule of law, it is doubtful that states even agree what the term really means.

Do-gooders and democrats try to convince dictators to improve rule of law, while repressive regimes are more than happy to refer to “rule of law” as they crack down on dissent at home. And governments of every stripe lean on rule of law arguments in the international arena.

With definitions so divergent, the meeting on the rule of law could end up being a forum in which everyone talks past each other, using the same words for wildly different things.

If this is to be a meaningful step toward more equitably governed states and a more reliably rules-based international system, then we have to first agree what it is we are actually talking about — particularly in this forum, as it will likely become an important platform for donor funding.

In our eagerness to promote the rule of law, we often confuse three competing visions of it: the institutional, the procedural and the substantive.

The institutional rule of law is the most familiar. It is concerned mainly with law enforcement and stresses security and security institutions. In fact, we should call it “law and order” rather than the rule of law.

The rule of law in the procedural sense reflects a formal understanding of the concept, and emphasizes the preference for rules over human arbitrariness. The rules themselves are subject to formal requirements, designed to further restrict inconsistent application: The laws must be public; they must have been properly enacted by a competent authority; they must not be retroactive; and it must be possible to comply with them.

We could call this “rule by law”, which encompasses the acclaimed principle that “no one is above the law”. Like the idea of “law and order”, “rule by law” has a certain attraction. It conveys a sense of fairness and of protection from the capricious exercise of power. Yet it says nothing as to the law’s content, being concerned only with form.

Both concepts fall short of what the modern understanding of the rule of law should offer.

The real rule of law is substantive and encompasses many human-rights requirements. It reflects the idea of equality in a substantive way: not just that no one is above the law, but that everyone is equal before and under the law, and is entitled to its equal protection and equal benefit.

Only this concept of the rule of law would prevent a law being enacted to regulate the use of torture, for example. Even if properly promulgated and equitably enforced, such a law would still fail under the substantive requirements of the rule of law. Properly understood in this fashion, the rule of law would also prohibit the enactment of a law that would deprive women of the right to vote, or otherwise offend fundamental human rights guarantees.

Under this substantive understanding, rules serve a higher purpose than the mere orderly regulation of human conduct; laws must also enhance liberty, security and equality and strive to attain a perfect balance between law and justice.

This is a tall agenda at both the national and the international levels, but it is the one that the rule of law commands. It requires that laws be just, and justly enforced.

An endorsement of the “rule by law” or the “law and order” model — rather than the real, substantive rule of law — does not merely fall short of its objective. It runs the risk of subverting its purpose entirely.

The robust enforcement of laws that violate fundamental human rights can entrench authoritarians and even give them a veneer of respectability.

There could be no worse perversion of a legal and political concept that holds so much for the advancement of individual freedom and of proper collective governance.

In 1848, Henri-Dominique Lacordaire, the French priest and political activist, rightly noted, “Between the strong and the weak, between the rich and the poor, between master and servant, it is freedom that oppresses and the law that sets free.”

The purpose of law in a free and democratic society is to liberate, not to restrain. It is to create a safe and just environment in which human conduct is regulated, and power is constrained so that maximum freedom and safety is attained by all.

Louise Arbour

former U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights

Read the original article in the NYT