The news about Chinese economic growth, though slowed by macroeconomic imbalances, overall indebtedness and the “trade war” with the US, confirm the extent of the results achieved by President Xi Jinping at the domestic level as the Chinese Communist Party has a firmer grip on power: power which has been accumulated by one man, a President with no term limits and free – at least apparently – from any form of internal opposition. The “neo-imperial” transformation of Chinese power, the successes obtained in science and technology (artificial intelligence, quantum computing, space and weapons of the latest generation), often through the misappropriation of data from companies and western researchers, was supported by a globalization unquestionably favourable to China. Nevertheless, the debate that is developing in several western countries mirror an enthusiastic and unconditional acceptance of Beijing theories, magnifying the great benefits linked to Chinese funding and even the “superiority” of the Chinese social, political and ideological model as compared to the Western Rule of Law.

Against this background, Beijing’s commercial, financial, military and diplomatic initiatives proceed with a “crescendo” in which the great Russian military drill of last summer – three hundred thousand soldiers, one thousand tanks, hundreds of planes and integrated Sino-Russian controls – fits perfectly. Not to mention the increasingly frequent and enthusiastic meetings between Putin and Xi: the two leaders enjoy the prvilege to address each other as “best friend”, almost reaching a “sanctification” that excites some – not always disinterested – exegetes of the Chinese way and Euroasian values. Indeed, many Asian, Middle Eastern, African countries and governments, and European politicians and entrepreneurs as well, are eager to open up to Chinese funds with “no conditions”, negotiated neglecting the fight against corruption and with no guarantees of social security nor labor rights.

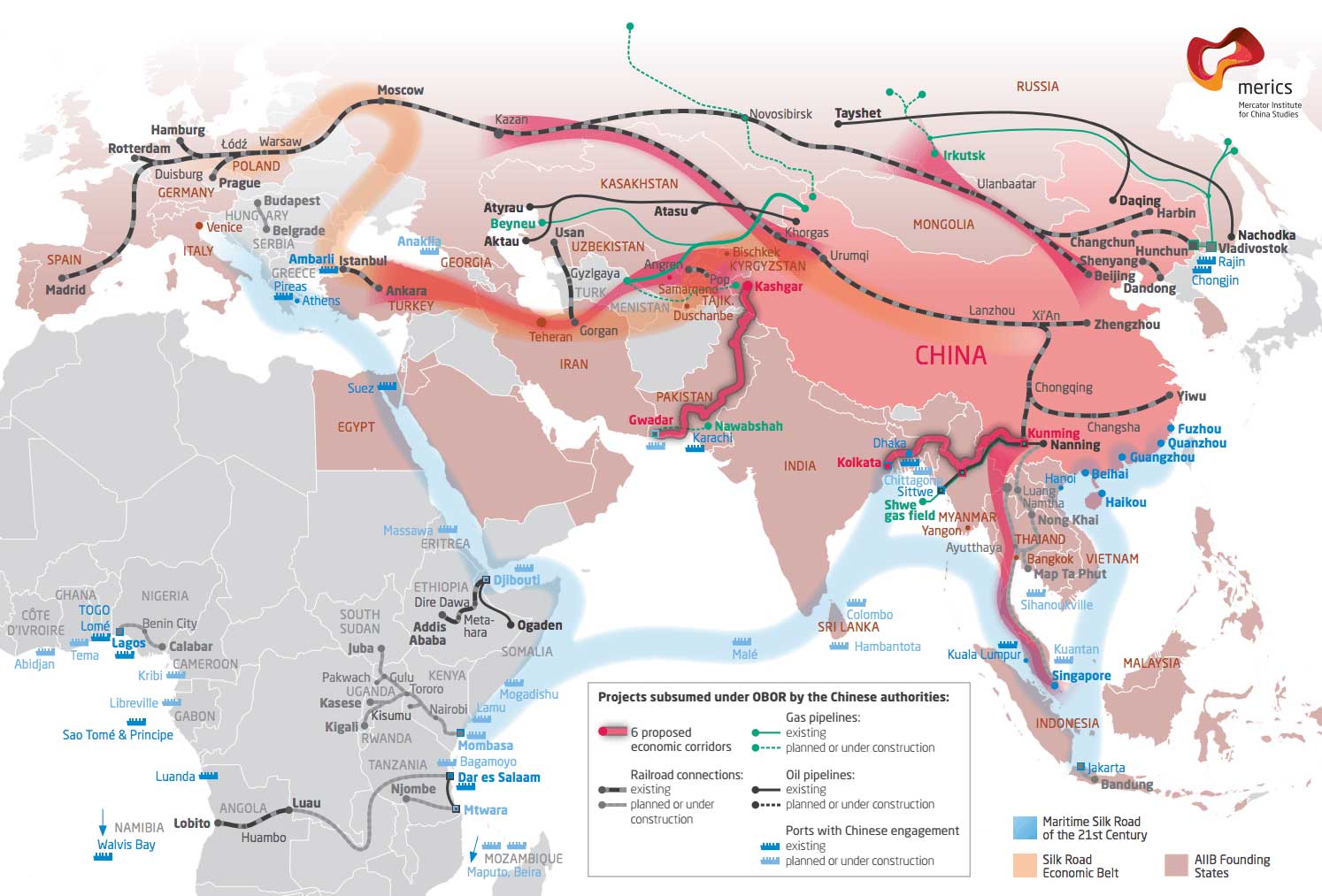

Beijing’s plan presents all the ingredients of a geopolitical project for a “new world order” in which China intends to assume the role of superpower: a project that comes from afar, but which now assumes a marked assertiveness in statements, documents, diplomatic, commercial and military initiatives taken under Xi Jinping’s China. What are the reasons behind Beijing’s continuous expansions, from the initial Eurasian and African context (terrestrial and maritime “Silk Roads“) to the “Silk Road in the Pacific”, from the “Silk Road on the ice” in the Arctic, to the latest “Digital Silk Road” through cyber space?

The Chinese press – certainly not to new to the cult of personality – has branded these initiatives as “the journey of Xi Jinping”, while solliciting foreign governments to show appreciation towards China so as to feed the internal propaganda. With wealth and successes, the capacity of attraction of the Chinese model has gone up, however doubts are on the rise as far as Beijing’s desiderata are concerned, even in countries like Myanmar, for decades considered politically and economically under China’s influence. For example, authorities are wondering what is the interest of Myanmar in the construction of the Kyaukphyu port, in the Bay of Bengal, with the attached “Special Economic Zone”, coming at the astronomical cost of $7.3 billion, financed by a conglomerate of the Chinese state, holding a 70% share and the management for fifty years: the port would be of enormous value for China, in that it would provide sea access to the important Yunnan Province, thusd allowing Chinese merchant and military ships to break free from the Strait of Malacca.

How the Chinese loan will be paid off, considering that Myanmar holds a 30% quota, remains to be seen. Everyone knows what happened last year with the Chinese funding for the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka, which slipped directly under Chinese control including 69 Kmq of surrounding territory (!) because the local government was not able to honor the debt. In recent months, a particularly authoritative think-tank dealing with sustainable development, the “Center for Global Development“, published research on eight countries deemed at high risk of “financial collapse” due to the indebtedness with to China: Laos, Kyrgyzstan, Maldives, Montenegro, Djibouti, Tajikistan, Mongolia and Pakistan; in less than two years, following the involvement in Chinese projects, the debt/GDP ratio of those countries has gone up respectively (starting with Laos) from about 50% to 70%; from 23% to 74%; from 39% to 75%; from 10% to 42%; from 80% to 95%; from 55% to 80%; from 40% to 58%; from 12% to 48%.

In Montenegro, a highway financed by Beijing configures as a one-sided pact, since the amount of the debt is tantamount to a quarter of the entire GDP of the country (!). In Laos, a railway line is as much as half of the country’s annual GDP. It is estimated that in the period 2000-2014 the Chinese Government has financed projects amounting to 354 billion dollars. President Trump has described “predatory” such initiatives and Christine Lagarde, Executive Director of the International Monetary Fund, has highlighted several problematic issues, hoping that “the Belt and Road Initiative will develop only where it is really necessary”.

The most pressing concerns relate to the conditions that the Government and the Chinese state-bodies are able to exercise in Europe, particularly in Italy, whenever Beijing intends to acquire companies of strategic value for our countries and for the brand “Made in Italy”. Such deals come at extremely disadvantageous conditions for the “Italian system”, for the economy and for the protection of data and technology endangered by the lack of any condition of reciprocity.

In early 2018, all EU Ambassadors but the Hungarian in Beijing signed off a report to Brussels warning against the challenge for free market rules posed by the new Chinese “silk roads”. The majority of Chinese investments in the European Union in 2017 come from state-owned companies and the most attractive sectors for Chinese capital are critical infrastructures of national importance in strategic sectors such as transport, energy and the digital sector.

Through state-run companies, China has access to information of national and European strategic relevance regarding investments closely linked to global geopolitical strategies, especially in the field of energy supply, patents and technological innovations including the digital and automation sectors. Europe is still lacking a real “shield” against intrusive investments hiding a political agenda and casting doubts whether foreign powers present in strategic sectors closely linked to national and European security should be therefore accepted in the cockpit.

Furthermore, Italian and European investments in China are strongly conditioned by market restrictions , which means that the principle of reciprocity is not in place, thus forcing Italian and European companies to compete on uneven ground that greatly benefits Chinese companies. Unlike the European Union, the United States have a system to review foreign investments, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which evaluates whether a given foreign investment can damage national security. In Europe a similar body does not exist. Currently, the European Commission is examining a proposal to set up a system of coordination of national screening systems.

In August, I heard senior political actors at the national and European level, supposedly concerned for the rule of law and the principles of liberal democracy enshrined in the Treaties, treating the Belt and Road Initiative and the New Silk Road as some sort of revealed truth, labelling them as the “Marshall Plan” of the millennium, slavishly echoing Beijing’s arguments and the propaganda. The recent separate missions to China by Finance Minister Tria, Deputy Prime Minister Di Maio and Undersecretary Geraci ended with emphatic statements on the important advantages deriving from Chinese take-overs in strategic sectors, mainly transport and technology.

Unfortunately, this trend is not new in the Italian political and business world. Our country has often shown eagerness to “be the first” to seize easy opportunities provided by extremely complex markets, in countries where market rules, respect for foreign investors, equality of treatment and reciprocity always come later, much later, following other priorities marked by ideological, nationalistic and even militaristic interests, as it was the case with Iran.

Trump, Macron, Merkel and May have serious concerns and are working on measures to put in place in order to protect their national interests: given the vital need to protect the “Made in Italy” in strategic companies as well as consumer goods and services, shouldn’t Italy too pay much more attention to their national interest and have a more objective assessment of the “Chinese question”?

Amb. Giulio Terzi