When the Scottish people were asked to vote in a historic referendum nearly six years ago to decide whether or not Scotland would be remaining part of the United Kingdom, 55.30% of voters expressed their disapproval, abandoning the dream of an independent Scotland. The primary aim of this article is to discuss the negotiation process that led Scotland and the UK to sign an agreement and make possible the holding of a referendum. Then, in the second section, the focus will be shifted towards the political and social events that Scotland is experiencing in the last period.

“Should Scotland be an independent country?” was the question to which Scots were called to answer in the 2014 referendum, but also an important decision that would affect the future of the nation and the institutional structure of the United Kingdom. Despite the negative result, the victory of the independence front would have put an end to three hundred long years of history, during which Scotland was incorporated into the United Kingdom of Great Britain with the adoption of the Union Acts in 1707. Although some essential features of the nationalism and the legal framework of Scotland were maintained, English influence was prevalent in the management and control of the internal affairs of the country. As a result, the desire for autonomy and separation from the United Kingdom started to emerge strongly.

The landslide victory of the Scottish National Party (SNP) in the parliamentary elections in 2011 revived the debate on the persistent issue of independence. At the heart of the political agenda of the Prime Minister of Scotland and leader of the SNP – Alex Salmond – there was the proposal of a referendum that would have allowed Scotland to become sovereign and independent if it had been successful. Before allowing voters to decide the future of their nation and express their opinion, a pre-referendum and negotiation phase between the governments of London and Edinburgh was necessary. According to Sections 1, 29 and 30 of the Scotland Act – namely the act of the British parliament that was issued in 1990 and it defined the powers of the Scottish parliament – emerges that the Scottish legislative body can neither legislate nor authorise a referendum on its independence. Moreover, as Schedule 5 of the same document reports, the matter concerning the “Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England” is a reserved matter, i.e. an area that falls in the exclusive competence of the UK Parliament.

Therefore, both the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Prime Minister of Scotland needed to reach an agreement that would temporarily transfer the right and the legal competences to hold a referendum to the Scottish Parliament. Despite the British nationalism of Cameron and his strong opposition to the secession of Scotland, the signing of the Edinburgh Agreement in 2012 not only marked the achievement of a political deal between the two governments but it also allowed to establish a legal and legitimate consultation, which was officially scheduled on 18 September 2014. An interesting aspect that is worth underlying is the choice of the date, which refers to the 700th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn during which the forces of King Robert I of Scotland defeated the English army during the wars of independence.

In addition to the negotiation process, the legal framework of the Scottish Independence Referendum (Franchise) Act and the Scottish Independence Referendum Act is a further aspect that deserves attention. Both adopted by the Scottish Parliament on 27 June 2013 and 14 November 2013, the first act contains the provisions regarding the subjects who are entitled to vote, while the second act sets out the date and the rules concerning the holding of the referendum and its campaigning. In more details, once the question to be presented to the electorate was elaborated, and the Electoral Commission specified that it must be clear, neutral and straightforward, the innovative aspect concerned the right to vote that was given for the first time to citizens with a minimum age of 16 and living in Scotland. Besides the activity of consulting, the same Commission was also responsible for ensuring the impartiality of the campaigning, which saw the two leading groups expose their arguments in favour and against independence.

In support of the independence, the Yes Scotland campaign, on the one hand, believed that the detachment from the United Kingdom would favour the Scottish economy and allow Edinburgh – and not London – to cash the proceeds deriving from the oil and gas industries, making Scotland a world leader in these sectors. Moreover, voting yes in the referendum would ensure a full decision-making autonomy to the Scottish parliament that would be thus able to define and develop its policies, without being forced to accept Westminster’s decisions passively. On the other hand, the pro-union Better Together campaign encouraged voters to remain part of the United Kingdom focusing on two main arguments, namely the existence of an emotional connection between Scotland and the UK and the growing economic uncertainty that Scotland would have faced in case it decided to leave the country.

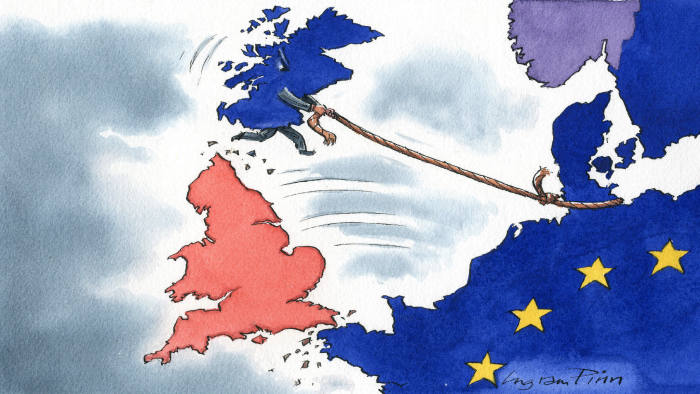

Today, the outcome of the 2014 referendum is well-known. With a gap of about 10% point, the Scottish people decided to stay in the United Kingdom. However, the referendum’s results of June 2016, and the approval of the Brexit deal by both Houses of Parliament, determined a “material change in circumstances”. Along with Northern Ireland, the will of Scotland is now twofold: to separate from the UK and stay in the European Union (EU). As the figure of Alex Salmond was emblematic in the 2014 referendum, it is Nicola Sturgeon, at present, to maintain relations with the UK government for the proclamation of a new referendum. Relying again on Section 30 of the Scotland Act, the Scottish First Minister and leader of the Scottish Nationalist Party called for a new referendum to Boris Johnson who, however, formally rejected the request.

As a result, on Saturday 11 January 2020 tens of thousands of people marched the streets of Glasgow in support of a Scotland free, anchored to the guarantees deriving from the membership to the EU and profoundly contrary to Brexit. On the same day, the pro-independence leading group that headed the event, i.e. the All Under One Banner movement, posted a video online in which it stressed the importance of ensuring the fundamental right of self-determination to Scotland. Codified in international treaties, such as the Charter of the United Nations in 1945 and the 1966 International Covenants on civil and political rights and economic, social and cultural rights, the right under consideration must be intended as the entitlement of states to choose their own “constitutional future”.

On that basis, preventing Scotland from holding a referendum is an indefensible choice because it is evident that it will negatively impact the exercise of Scotland’s right to self-determination. However, Richard Leonard – the current leader of the Labour party – proposed the creation of a federal UK as a third possible option to take into account whether a second referendum, concerning the institutional future of Scotland, will take place.

In summary, in the light of these recent events, and in case a second independence referendum is held in Scotland, the eventual victory of a “leave” could bring with it the risk of a strong internal dissolution.

Federica Donati